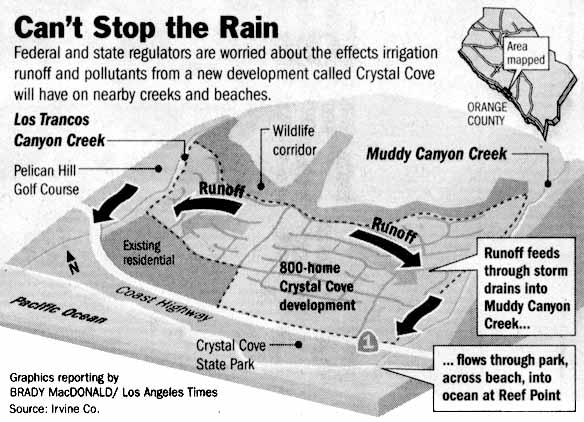

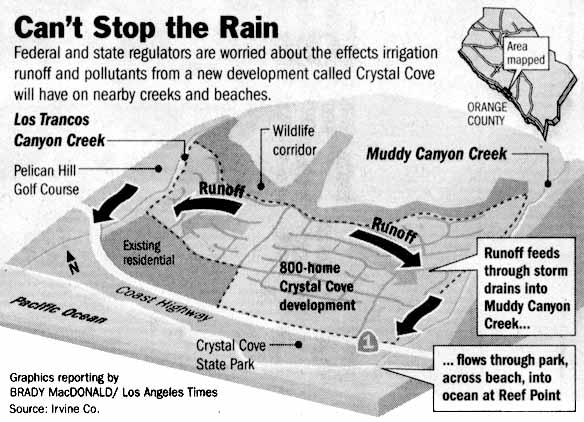

The Irvine Co. is proudly advertising Crystal Cove, its latest planned community, as an 800-home jewel set among 10,000 acres of carefully protected wild lands. But federal and state officials are sounding alarms about potential effects of the huge new development, being built upstream from the pristine Crystal Cove State Park, and are questioning a controversial approval that may be granted to the developer.

Overriding written objections from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Army Corps of Engineers said this week that once the project gains approval from state water quality officials, it plans to grant the Irvine Co. a permit to fill in or alter up to six miles of the Muddy Canyon and Los Trancos Canyon creeks and their tributaries.

A Fish and Wildlife memo says that is 600 times the length of stream bed that federal law allows to be affected under a national permitting process. But the Army Corps says it also considers the type of stream bed.

"That's huge--that's six miles. I don't remember anything this big," said Rebecca Tuden, the EPA analyst who reviewed and objected to the permit application. "This is not a minimal impact. We think it's going to have major effects downstream."

She said there could be irrevocable loss of plants and wildlife both within the development and on the parkland and beaches below. Most of the runoff from the development will be funneled into Muddy Canyon Creek, run through the state park, one of the largest remaining pieces of natural coastal terrain in Southern California, then spill into the Pacific Ocean.

Irvine Co. officials say the project is a sophisticated, environmentally sound one, with extensive measures for protection of wildlife and water.

"This is one of the most studied and carefully planned coastal communities in Southern California," spokesman Paul Kranhold said. "It's been in the planning stages for 30 years."

The first homes would be ready for sale in about a year.

He said a mile-wide wildlife corridor has been set aside inland at the top of the project area, along with other preserved lands, in exchange for the right to build the community of million-dollar homes.

Sat Tamaribuchi, vice president for environmental affairs, said that the six miles of affected stream bed was mostly a spider web of dry washes and ruts across the property that fill only right after storms and that less than three acres of wetland or active stream bed would be touched.

"That six miles sounds huge, but I would guess there's 100 miles of dry wash we're not touching," in the preserved areas, he said.

The site is being carved out of scenic hills on the inland side of Coast Highway between Corona del Mar and Laguna Beach. Drivers, joggers and bikers long used to birds wheeling above the bluffs are growing accustomed to other sights and sounds familiar in Orange County: the beep, beep, beep of heavy machinery backing up, the grind of bulldozers and the sprouting of construction trailers on the torn-up hills.

"It's a plague over everything," said Sid Wittenberg, a retired optometrist from Mission Viejo, as he hiked in the state park Friday. "These hills that turn from green to gold will be tiled rooftops instead. The season will be invisible."

Visitors also were dismayed at the Reef Point beach below, where at peak rainy times more than 10,000 gallons per second of urban runoff could run across the beach into the ocean.

"This is a spectacular place. It would be a shame to see it ruined," said Al Ziccardi, 62, a Scottsdale, Ariz., resident visiting his daughter in Orange County. "California has a number of treasures, and this is one of them. Once it's gone, it'll never come back."

Irvine Co. consultants, in an environmental impact report last year, said that while the residential, hotel and shopping center project would spoil some views from the state park, it would do minimal damage to streams and wildlife.

"While the people who use this property might be upset because they are viewing homes instead of hillsides," Kranhold said, "what they need to recognize is that the company as given up its development rights on 78% of the Newport Coast . . . in exchange for the right to develop in these small areas."

Tamaribuchi added: "We're building beautiful homes."

The company's environmental report concluded that water runs in the creeks only occasionally and that specially constructed drain pipes into Muddy Canyon Creek, along with a holding pond, could handle runoff, avoiding flooding and erosion below.

Also open to debate is how water quality will be affected by pesticides, fertilizers, pet waste and other urban runoff that will drain through the park, across the beach and into the ocean.

"Once they get all those homes built, the runoff from the gutters, the roofs, the streets has got nowhere to go but into the state park," said senior Crystal Cove Park Ranger Michael Eaton. "I'm worried that our tide pools may be buried."

Grading of the site in past years resulted in three-mile-long sediment plumes in the ocean, according to state park ecologist David Pryor. He said that could be beneficial, because it could add sand to the beach, but it could also have adverse effects.

"Worst-case scenario is we have to close down portions of the beach because of high bacteria" during the peak summer season, he said, because that is also when "nuisance" pollutants such as lawn fertilizers or oil from home garages could end up being dumped into the drainage system.

Some irrigation runoff is unavoidable, Tamaribuchi said. But much of the irrigation waste would dissipate on site, he said, because the company is altering relatively little of Muddy Canyon Creek and is creating additional wetlands.

Still, water quality control is the last large issue for the development. The Army Corps, which originally planned to issue a "nationwide permit" to the Irvine Co. on Friday, instead said it will deny it for now because the state water quality regional control board has not completed its approvals. The regional quality control board could not find its documents on the development. If those approvals come through, a nationwide permit will be granted, said Jae Chung, the Corps project manager handling the permit.

Nationwide permitting allows developers to win speedy approval from the Army Corps to alter federally protected waters, sidestepping lengthier analysis by the EPA, Fish and Wildlife and others.

"We have no recourse under nationwide permits," said Tuden of the EPA.

Tamaribuchi said the permit was appropriate because a minimal amount of federally protected waters would be affected.

Chung, who recommended approval of the permit, said he did not foresee a problem in terms of flooding or erosion as a result of the development. He said the Corps does not have jurisdiction over water quality issues.

As for the six miles of affected stream bed, he said the Corps had a policy that any changes to ephemeral streams, or those that only run after rainstorms, could exceed the legal 500-foot limit. He said only 450 feet of more active stream bed will be altered, and much of it will actually be preserved in its natural state or enhanced with new vegetation.

Chung said he had spoken with state ecologist Pryor about the potential impact on the park and beach, and Pryor had told him that his concerns had been addressed by the developer. Pryor said he recalled only a "brief" phone conversation with Chung, not specifically mentioning the nationwide permit. He said that it was up to the Corps, not him, to decide, but that he would have preferred more thorough analysis. Barring a full study, there is "no way to know" what effect the development will have on the park and the beach.

As for the other federal agencies' objections, Chung said, "We [the Corps] look at multiple options, not just environmental. We look at the economics as well. . . .Generally, we try to reach consensus [with an applicant]. . . . If we push too hard, they'll push back."

Irvine Co. exercises an unusual degree of control over the public park, as part of an agreement 20 years ago in which it sold land to the state for $32.6 million. In the deed, the company retained numerous easements, including extensive rights to build or alter drainage systems in the park.

So far, the developer plans only to improve a drain pipe already in the creek on state park property, Pryor said. But company officials could do "whatever they want," he said.

Another area that concerns all the regulators, including the Corps, is the mitigation offered by the Irvine Co.

Under the federal Clean Water Act, developers must replace disturbed wetlands or streams at other comparable sites. The Irvine Co. wants to use portions of the San Joaquin marshes, in the city of Irvine several miles away. Regulators said the developer has used the San Joaquin site in the past and done it improperly. Fish and Wildlife, EPA and Army Corps officials all said a stand of one species of tree had been planted, not adequate replacement for whole ecosystems.

"It's horrible," Tuden said of the proposal. "Basically, they're taking a flowing stream with a certain habitat and plants . . . and trading it for a tree farm."

The top officer of the Army Corps' Los Angeles office also told the Irvine Co. in March 1998 that there had been problems with the San Joaquin mitigation.

Irvine officials said that while the original work done at the marsh might have focused only on trees, that was no longer the case.

Chung said mitigation was still being "actively negotiated" and the San Joaquin marsh might end up being used to satisfy part of the legal requirement.

The 800 homes and upscale shopping center are one phase of an eventual 2,600 homes to be developed along the Newport Coast by the Irvine Co. In addition, a 1,000-room Marriott Hotel being built above the Irvine development will drain into Los Trancos Creek, down through the park into the ocean.

Of the multiple developments, Pryor said: "We can only guess what effects there are going to be."

.

[Clips from original newspaper articles appear here for educational purposes and purposes of comment, rather than commercial purposes. They are reprinted under the fair use doctrine of international copyright law. Copyright Los Angeles Times]

.

http://www.EMIT.org